The secret of the “Chinese” scrollThe scroll’s life story is shrouded in mystery.

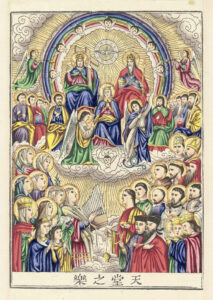

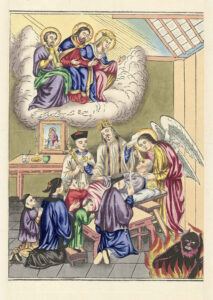

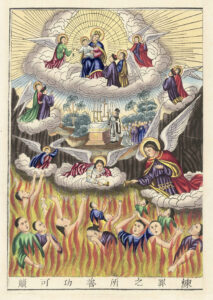

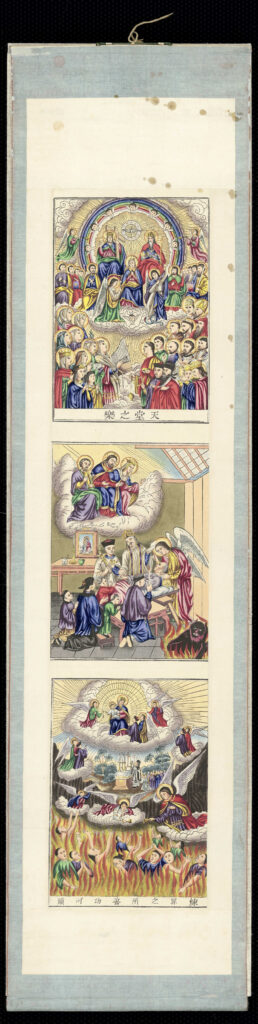

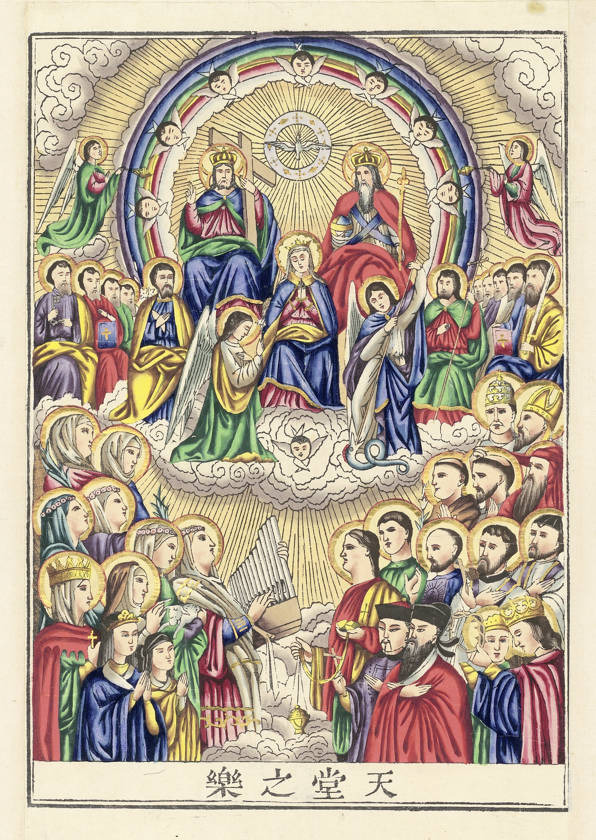

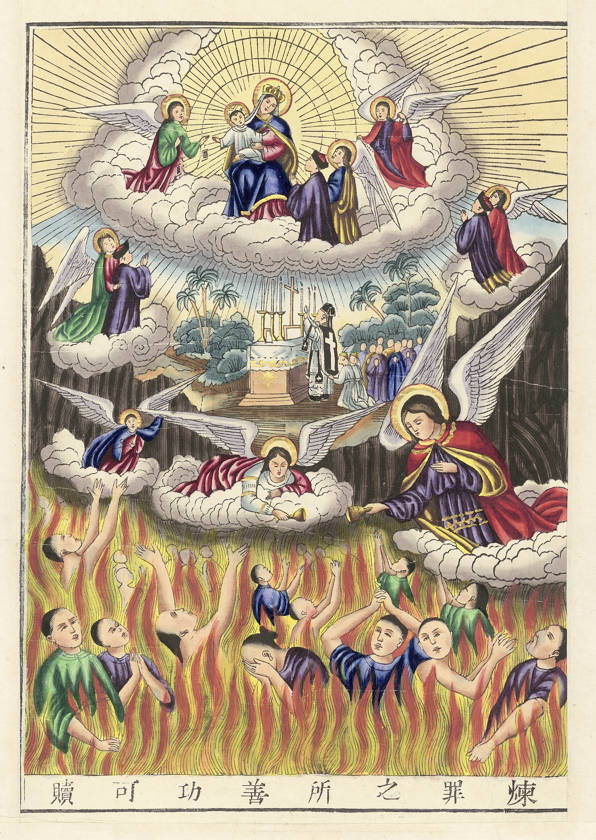

At first glance, the missionary scroll from the Celje Regional Museum resembles a Chinese painting, pasted onto a silk base and with round wooden sticks at the top and bottom ends. The sticks were intended for the scroll to be kept rolled up, which was a common practice of storing paintings in China. However, the scroll is just as Chinese as it is European, and it testifies to the depth of the intellectual and artistic contacts between Europe and Asia. The three woodcut images with inscriptions in Chinese depict Catholic religious scenes, which reveals that the scroll came into being within the scope of Catholic missionary activities in China.

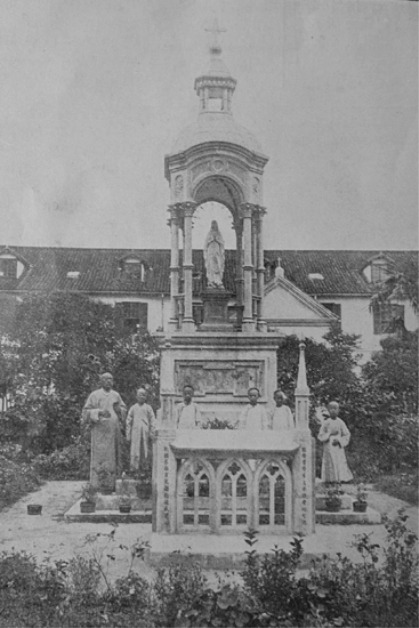

The scroll is just as Chinese as it is European, and it testifies to the depth of the intellectual and artistic contacts between Europe and Asia. The scroll’s life story is shrouded in mystery. The images were woodblock printed and then meticulously hand painted with watercolours, their distinct style suggesting the scroll may have been produced at the Tushanwan Jesuit workshops located on the outskirts of Shanghai. Little is known about the exact time of its production, the ways it travelled thousands of kilometres and survived so well preserved for more than a century of turbulent Slovene history.

The only hint on how old it may be is provided by the inscription on the back of the scroll. A semi-legible pencil note reads:

Mission Anstalt [unreadable] bei Shanghai Shanghai 3/5 1883 [unreadable]

The information about the “mission station” that was “near Shanghai” matches the scroll’s style and motifs, which are characteristic of the Tushanwan workshops. Unfortunately, it is not known who wrote this German note on the back of the scroll in May 1883, nor whether it was the same person who brought the scroll to Celje or its surroundings. Two rather frustrating facts contribute to the mystery. The first one is that there are no records on Slovene missionaries in China during this period. Joseph von Haas from Mozirje worked at the Austro-Hungarian consulate in Shanghai at the time, and the legacy of his widow Eleonora was partially lost after her death during World War II. The second one is that the scroll came to the Celje Regional Museum from the Federal Collection Centre as one of the objects confiscated after the war. Unfortunately, no records on its owners prior to confiscation have been found to date.